No. Please don’t. It does little for security but harms productivity (because staff spend ages pondering emails, and not answering legitimate ones), upsets staff and destroys trust within an organisation.

Why is phishing a problem?

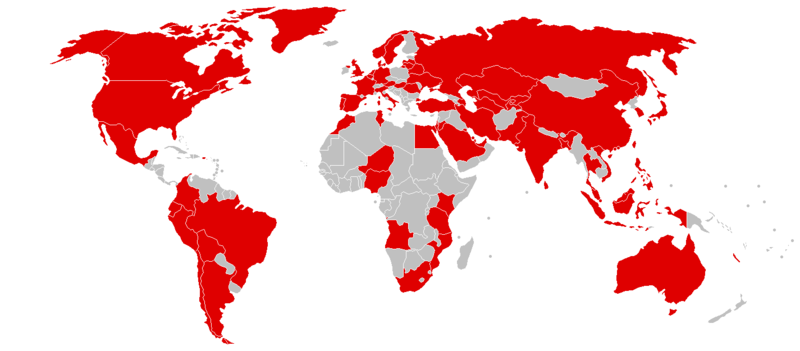

Phishing is one of the more common ways by which criminals gain access to companies’ passwords and other security credentials. The criminal sends a fake email to trick employees into opening a malware-containing attachment, clicking on a link to a malicious website that solicits passwords, or carrying out a dangerous action like transferring funds to the wrong person. If the attack is successful, criminals could impersonate staff, gain access to confidential information, steal money, or disrupt systems. It’s therefore understandable that companies want to block phishing attacks.

Perimeter protection, such as blocking suspicious emails, can never be 100% accurate. Therefore companies often tell employees not to click on links or open attachments in suspicious emails.

The problem with this advice is that it conflicts with how technology works and employees getting their job done. Links are meant to be clicked on, attachments are meant to be opened. For many employees their job consists almost entirely of opening attachments from strangers, and clicking on links in emails. Even a moderately well targeted phishing email will almost certainly succeed in getting some employees to click on it.

Companies try to deal with this problem through more aggressive training, particularly sending out mock phishing emails that exhibit some of the characteristics of phishing emails but actually come from the IT staff at the company. The company then records which employees click on the link in the email, open the attachment, or provide passwords to a fake website, as appropriate.

The problem is that mock-phishing causes more harm than good.

What harm does mock-phishing cause?

I hope no company would publicly name and shame employees that open mock-phishing emails, but effectively telling your staff that they failed a test and need remedial training will make them feel ashamed despite best intentions. If, as often recommended, employees who repeatedly open mock-phishing emails will even be subject to disciplinary procedures, not only will mock phishing lead to stress and consequent loss of productivity, but it will make it less likely that employees will report when they have clicked on a real phishing email.

Alienating your employees in this way is really the last thing a company should do if it wants to be secure – something Adams & Sasse pointed out as early as 1999. It is extremely important that companies learn when a phishing email has been opened, because there is a lot that can be done to prevent or limit harm. Contrary to popular belief, attacks don’t generally happen “at the speed of light” (it took three weeks for the Target hackers to steal data, from the point of the initial breach). Promptly cleaning potentially infected computers, revoking compromised credentials, and analysing network logs, is extremely effective, but works only if employees feel that they are on the same side as IT staff.

More generally, mock-phishing conflicts with and harms the trust relationship between the company and employees (because the company is continually probing them for weakness) and between employees (because mock-phishing normally impersonates fellow employees). Kirlappos and Sasse showed that trust is essential for maintaining employee satisfaction and for creating organisational resilience, including ability to comply with security policies. If unchecked, prolonged resentment within organisation achieves exactly the opposite – it increases the risk of insider attacks, which in the vast majority of cases start with disgruntlement.

There are however ways to achieve the same goals as mock phishing without the resulting harm.

Measuring resilience against phishing

Companies are right to want to understand how vulnerable they are to attack, and mock-phishing seems to offer this. One problem however is that the likelihood of opening a phishing email depends mainly on how well it is written, and so mock-phishing campaigns tell you more about the campaign than the organisation.

Instead, because every organisation inevitably receives many phishing emails, companies don’t need to send out their own. Use “genuine” phishing emails to collect the data needed, but be careful not to deter reporting. Realistically, however, phishing emails are going to be opened regardless of what steps are taken (short of cutting off Internet email completely). So organisations’ security strategy should accommodate this.

Reducing vulnerability to phishing

Following mock-phishing with training seems like the perfect time to get employees’ attention, but is this actually an ineffective way to reduce an organisations’ vulnerability to phishing. Caputo et. al tried this out and found that training had no significant effect, regardless of how it was phrased (using the latest nudging techniques from behavioural economists, an idea many security practitioners find very attractive). In this study, the organisation’s help desk staff was overwhelmed by calls from panicked employees – and when told it was a “training exercise”, many expressed frustration and resentment towards the security staff that had tricked them. Even if phishing prevention training could be made to work, because the activity of opening a malicious email is so close to what people do as part of their job, it would disrupt business by causing employees to delete legitimate email or spend too long deciding whether to open them.

A strong, unambiguous, and reliable cue that distinguishes phishing emails from legitimate ones would help, but until we have secure end-to-end encrypted and authenticated email, this isn’t possible. We are left with the task of designing security systems accepting that some phishing emails will be opened, rather than pretending they won’t be and blaming breaches on employees that fail to meet an unachievable bar. If employees are consistently being told that their behaviour is not good enough but not being given realistic and actionable advice on how to do better, it creates learned helplessness, with all the negative psychological consequences.

Comply with industry “best-practice”

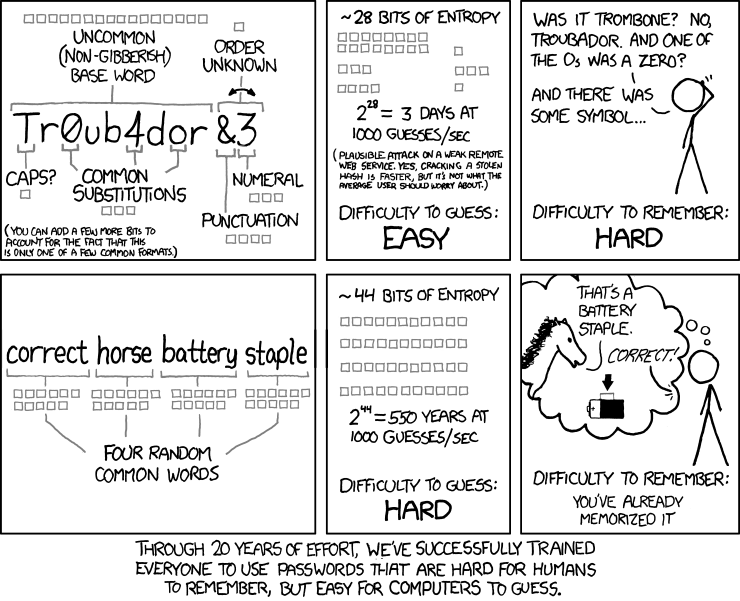

Something must be done to protect the company; mock-phishing is something, therefore must must be done. This perverse logic is the root cause of much poor security, where organisations think they must comply with so-called “best practice” – seldom more than out-of-date folk tradition – or face penalties when there is a breach. It’s for this reason that bad security guidance persists long after it has been shown to be ineffective, such as password complexity rules.

Compliance culture, where rules are blindly followed without there being evidence of effectiveness, is one of the worst reasons to adopt a security practice. We need more research on how to develop technology that is secure and that supports an organisation’s overall goals. We know that mock-phishing is not effective, but what’s the right combination of security advice and technology that will give adequate protection, and how do we adapt these to the unique situation of each company?

What to do instead?

The security industry should take the lead of the aerospace industry and recognise the “blame and train” isn’t an effective or acceptable strategy. The attraction of mock phishing exercises to security staff is that they can say they are “doing something”, and like the idea of being able to measure behaviour change as a result of it – even though research points the other way. If vendors claim they have examples of mock phishing training reducing clicks on links, it is usually because employees have been trained to recognise only the vendor’s mock phishing emails or are frightened into not clicking on any links – and nobody measures the losses that occur because emails from actual or potential customers or suppliers are not answered. “If security doesn’t work for people, it doesn’t work.”

When the CIO of a merchant bank found that mock phishing caused much anger and resentment from highly paid traders, but no reduction in clicking on links, he started to listen to what it looked like from their side. “Your security specialists can’t tell if it is a phishing email or not – why are you expecting me to be able to do that?” After seeing the problem from their perspective, he added a button to the corporate mail client labeled “I’m not sure” instead, and asked staff to use the button to forward emails they were not sure about to the security department. The security department then let the employee know, plus list all identified malicious emails on a web site employees could check before forwarding emails. Clicking on phishing links dropped to virtually zero – plus staff started talking to each other about phishing emails they had seen, and what the attacker was trying to do.

Security should deal with the problems that actually face the company; preventing phishing wouldn’t have stopped recent ransomware attacks. Assuming phishing is a concern then, where possible to do so with adequate accuracy, phishing emails should be blocked. Some will get through, but with well engineered and promptly patched systems, harm can be limited. Phishing-resistant authentication credentials, such as FIDO U2F, means that stolen passwords are worthless. Common processes should be designed so that the easy option is the secure one, giving people time to think carefully about whether a request for an exception is legitimate. Finally, if malware does get onto company computers, compartmentalisation will limit damage, effective monitoring facilitates detection, and good backups allow rapid recovery.

An earlier version of this article was previously published by the New Statesman.