For many gay and bisexual men, mobile dating or “hook-up” apps are a regular and important part of their lives. Many of these apps now ask users for HIV status information to create a more open dialogue around sexual health, to reduce the spread of the virus, and to help fight HIV related stigma. Yet, if a user wants to keep their HIV status private from other app users, this can be more challenging than one might first imagine. While most apps provide users with the choice to keep their status undisclosed with some form of “prefer not to say” option, our recent study which we describe in a paper being presented today at the ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing 2018, finds privacy may “unravel” around users who choose this non-disclosure option, which could limit disclosure choice.

Privacy unraveling is a theory developed by Peppet in which he suggests people will self-disclose their personal information when it is easy to do so, low-cost, and personally beneficial. Privacy may then unravel around those who keep their information undisclosed, as they are assumed to be “hiding” undesirable information, and are stigmatised and penalised as a consequence.

In our study, we explored the online views of Grindr users and found concerns over assumptions developing around HIV non-disclosures. For users who believe themselves to be HIV negative, the personal benefits of disclosing are high and the social costs low. In contrast, for HIV positive users, the personal benefits of disclosing are low, whilst the costs are high due to the stigma that HIV still attracts. As a result, people may assume that those not disclosing possess the low gain, high cost status, and are therefore HIV positive.

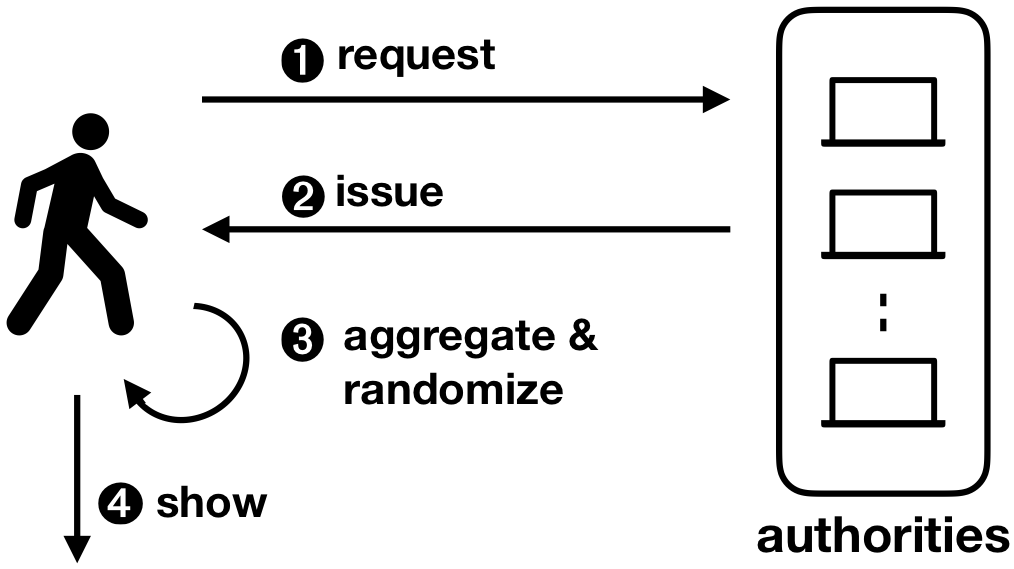

We developed a series of conceptual designs that utilise Peppet’s proposed limits to privacy unraveling. One of these designs is intended to artificially increase the cost of disclosing an HIV negative status. We suggest time and financial as two resources that could be used to artificially increase disclosure cost. For example, users reporting to be HIV negative could be asked to watch an educational awareness video on HIV prior to disclosing (time), or only those users who had a premium subscription could be permitted to disclose their status (financial). An alternative (or in parallel) approach is to reduce the high cost of disclosing an HIV positive status by designing in mechanisms to reduce social stigma around the condition. For example, all users could be offered the option to sign up to “living stigma-free” which could also appear on their profile to signal others of their pledge.

Another design approach is to create uncertainty over whether users are aware of their own status. We suggest profiles disclosing an HIV negative status for more than 6 months be switched automatically to undisclosed unless they report a recent HIV test. This could act as a testing reminder, as well as increasing uncertainty over the reason for non-disclosures. We also suggest increasing uncertainty or ambiguity around HIV status disclosure fields by clustering undisclosed fields together. This may create uncertainty around the particular field the user is concerned about disclosing. Finally, design could be used to cultivate norms around non-disclosures. For example, HIV status disclosure could be limited to HIV positive users, with non-disclosures then assumed to be a HIV negative status, rather than HIV positive status.

In our paper, we discuss some of the potential benefits and pitfalls of implementing Peppet’s proposed limits in design, and suggest further work needed to better understand the impact privacy unraveling could have in online social environments like these. We explore ways our community could contribute to building systems that reduce its effect in order to promote disclosure choice around this type of sensitive information.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 675730.