On July 2nd, 2017, Donald Trump, the President of the United States of America, tweeted a short video clip of him punching out a CNN logo. The video was modified from an appearance that Mr. Trump made at a Wrestlemania event. It originally appeared on Reddit’s /r/The_Donald subreddit. Although The_Donald was infamous in some circles, the uproar the image caused was many’s first introduction to a community of users that have had a striking amount of influence on the world stage. While memes like the one birthed from The_Donald are worrying, but mostly harmless, a shocking amount of disinformation (“fake news”) is also created by and spread from smaller, fringe Web communities that have relatively outsized influence on the greater Web.

#FraudNewsCNN #FNN pic.twitter.com/WYUnHjjUjg

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 2, 2017

In a nutshell, the explosion of the Web has commoditized the creation of false information and enabled it to spread like wild fire at unprecedented scale. After a decade and a half of experience with social media platforms, bad actors have honed their techniques and been surprisingly adept at crafting messages that at best make it difficult to distinguish between fact and fiction, and at worst propagate dangerous falsehoods.

While recent discourse has tried to blur the lines between real and fake news, there are some fundamental differences. For example, the simple fact that fake news has to be created in the first place. Real news, even opinion pieces, is based around reporting and interpretation of factual material. Not to dismiss the efforts of journalists, but, the fact remains: they are not responsible for generating stories from whole cloth. This is not the case with the type of misinformation pushed by certain corners of the Web.

Consider recent events like the death of Heather Heyer during the Charlottesville protests earlier this year. While facts had to be discovered, they were facts, supported by evidence gathered by trained professionals (both law enforcement and journalists) over a period of time. This is real news. However, the facts did not line up with the far right political ideology espoused on 4chan’s /pol/ board (or if we want to play Devil’s Advocate, it made for good trolling material), and thus its users set about creating alternative narratives. Immediately they began working towards a shocking, to the uninitiated, nearly singular goal: deflect from the fact that a like mind committed a heinous act of violence in any way possible.

4chan: Crowdsourced Opposition Intelligence

With over a year of observing, measuring, and trying to understand the rise of the alt-right online we saw a familiar pattern emerge: crowdsourced opposition intelligence.

/pol/ users mobilized in a perverse, yet fascinating, use of the Web. Dozens of, often conflicting, discussion threads putting forth alternative theories of Ms. Heyer’s killing, supported by everything from pure conjecture, to dubious analysis of mobile phone video and pictures, to impressive investigations discovering personal details and relationships of victims and bystanders. Over time, pieces of the fabrication were agreed upon and tweaked until it resembled in large part a plausible, albeit eyebrow raising, false reality ready for consumption by the general public. Further, as bits of the narrative are debunked, it continues to evolve, weeks after the actual facts have been established.

The Web Centipede

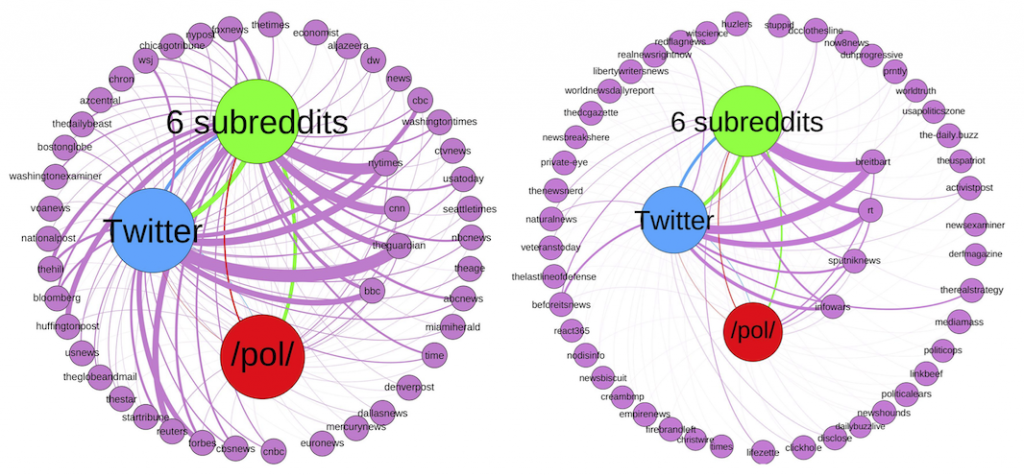

There are many anecdotal examples of smaller communities on the Web bubbling up and influencing the rest of the Web, but the plural of anecdote is not data. The research community has studied information diffusion on specific social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, and indeed each of these platforms is under fire from government investigations in the US, UK, and EU, but the Web is much bigger than just Facebook and Twitter. There are other forces at play, where false information is incubated and crafted for maximum impact before it reaches a mainstream audience. Thus, we set out to measure just how this influence flows in a systematic and methodological manner, analyzing how URLs from 45 mainstream and 54 alternative news sources are shared across 8 months of Reddit, 4chan, and Twitter posts.

While we made many interesting findings, there are a few we’ll highlight here:

- Reddit and 4chan post mainstream news URLs at over twice the rate than Twitter does, and 4chan in particular posts alternative news URLs at twice the rate of Twitter and Reddit.

- We found that alternative news URLs spread much faster than mainstream URLs, perhaps an artifact of automated bots.

- While 4chan was usually the slowest to a post a given URL, it was also the most successful at “reviving” old stories: if a URL was re-posted after a long period of time, it probably showed up on 4chan originally.

Measuring Influence Through the Lens of Mainstream and Alternative News

While comparative analysis of news URL posting behavior provides insight into how Web communities connect together like a centipede through which information flows, it is not sufficiently powerful to quantify the specific levels of influence they have.

Continue reading How 4chan and The_Donald Influence the Fake News Ecosystem