Social media data enables researchers to understand current events and human behavior with unprecedented ease and scale. Yet, researchers often violate user privacy when they access, process, and store sensitive information contained within social media data.

Social media has proved largely beneficial for research. Studies measuring the spread of COVID-19 and predicting crime highlight the valuable insights that are not possible without the Big Data present on social media. Lurking within these datasets, though, are intimate personal stories related to sensitive topics such as sexual abuse, pregnancy loss, and gender transition— both anonymously and in identifying ways.

In our latest paper presented at the 2025 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, “SoK: A Privacy Framework for Security Research Using Social Media Data,” we examine the tensions in social media research between pursuing better science enabled by social media data and protecting social media users’ privacy. We focus our efforts on security and privacy research as it can involve sensitive topics such as misinformation, harassment, and abuse as well as the need for security researchers to be held to a higher standard when revealing vulnerabilities that impact companies and users.

Methodology

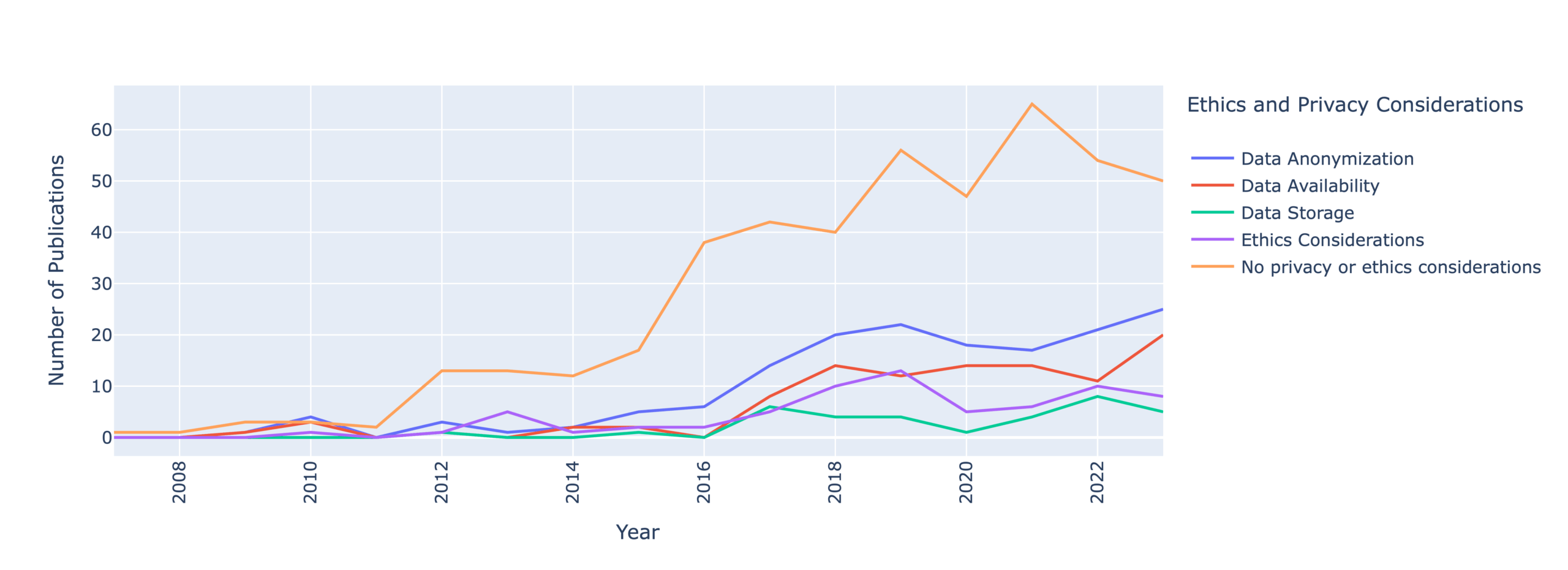

Toward this end, we conducted a systematic literature review of security literature on social media. We collected over 10,000 papers from six different disciplines, Computer Security and Cryptography (CSC), Data Mining and Analysis (DMA), Human-Computer Interaction (HCI), Humanities, Literature & Arts, Communication, (HLAC), Social Sciences, Criminology (SSC), and Social Sciences, Forensic Science (SSFS). Our final dataset included 601 papers across 16 years after iterating through several screening rounds.

How do security researchers handle privacy of social media data?

Our most alarming finding is that only 35% of papers mention any considerations of data anonymization, availability, and storage. This means that security and privacy researchers are failing to report how they handle user privacy.

Continue reading A Privacy Framework for Research Using Social Media Data