As social networks are increasingly relied upon to engage with people worldwide, it is crucial to understand and counter fraudulent activities. One of these is “like farming” – the process of artificially inflating the number of Facebook page likes. To counter them, researchers worldwide have designed detection algorithms to distinguish between genuine likes and artificial ones generated by farm-controlled accounts. However, it turns out that more sophisticated farms can often evade detection tools, including those deployed by Facebook.

What is Like Farming?

Facebook pages allow their owners to publicize products and events and in general to get in touch with customers and fans. They can also promote them via targeted ads – in fact, more than 40 million small businesses reportedly have active pages, and almost 2 million of them use Facebook’s advertising platform.

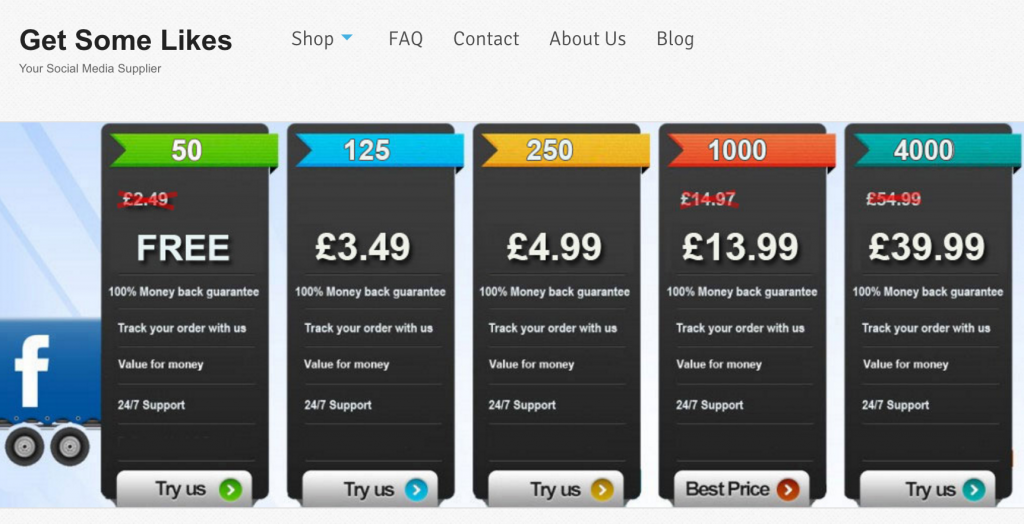

At the same time, as the number of likes attracted by a Facebook page is considered a measure of its popularity, an ecosystem of so-called “like farms” has emerged that inflate the number of page likes. Farms typically do so either to later sell these pages to scammers at an increased resale/marketing value or as a paid service to page owners. Costs for like farms’ services are quite volatile, but they typically range between $10 and $100 per 100 likes, also depending on whether one wants to target specific regions — e.g., likes from US users are usually more expensive.

How do farms operate?

There are a number of possible way farms can operate, and ultimately this dramatically influences not only their cost but also how hard it is to detect them. One obvious way is to instruct fake accounts, however, opening a fake account is somewhat cumbersome, since Facebook now requires users to solve a CAPTCHA and/or enter a code received via SMS. Another strategy is to rely on compromised accounts, i.e., by controlling real accounts whose credentials have been illegally obtained from password leaks or through malware. For instance, fraudsters could obtain Facebook passwords through a malicious browser extension on the victim’s computer, by hijacking a Facebook app, via social engineering attacks, or finding credentials leaked from other websites (and dumped on underground forums) that are also valid on Facebook.

Continue reading On the hunt for Facebook’s army of fake likes