In late 2009, my colleagues and I discovered a serious vulnerability in EMV, the most widely used standard for smart card payments, known as “Chip and PIN” in the UK. We showed that it was possible for criminals to use a stolen credit or debit card without knowing the PIN, by tricking the terminal into thinking that any PIN is correct. We gave the banking industry advance notice of our discovery in early December 2009, to give them time to fix the problem before we published our research. After this period expired (two months, in this case) we published our paper as well explaining our results to the public on BBC Newsnight. We demonstrated that this vulnerability was real using a proof-of-concept system built from equipment we had available (off-the shelf laptop and card reader, FPGA development board, and hand-made card emulator).

After the programme aired, the response from the banking industry dismissed the possibility that the vulnerability would be successfully exploited by criminals. The banking trade body, the UK Cards Association, said:

“We believe that this complicated method will never present a real threat to our customers’ cards. … Neither the banking industry nor the police have any evidence of criminals having the capability to deploy such sophisticated attacks.”

Similarly, EMVCo, who develop the EMV standards said:

“It is EMVCo’s view that when the full payment process is taken into account, suitable countermeasures to the attack described in the recent Cambridge Report are already available.”

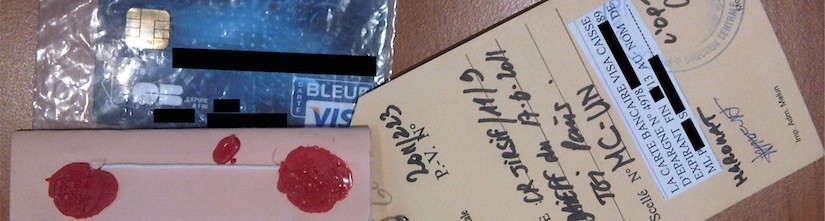

It was therefore interesting to see that in May 2011, criminals were caught having stolen cards in France then exploiting a variant of this vulnerability to buy over €500,000 worth of goods in Belgium (which were then re-sold). At the time, not many details were available, but it seemed that the techniques the criminals used were much more sophisticated than our proof-of-concept demonstration.

We now know more about what actually happened, as well as the banks’ response, thanks to a paper by the researchers who performed the forensic analysis that formed part of the criminal investigation of this case. It shows just how sophisticated criminals could be, given sufficient motivation, contrary to the expectations in the original banking industry response.

Continue reading Just how sophisticated will card fraud techniques become?