Social media data enables researchers to understand current events and human behavior with unprecedented ease and scale. Yet, researchers often violate user privacy when they access, process, and store sensitive information contained within social media data.

Social media has proved largely beneficial for research. Studies measuring the spread of COVID-19 and predicting crime highlight the valuable insights that are not possible without the Big Data present on social media. Lurking within these datasets, though, are intimate personal stories related to sensitive topics such as sexual abuse, pregnancy loss, and gender transition— both anonymously and in identifying ways.

In our latest paper presented at the 2025 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, “SoK: A Privacy Framework for Security Research Using Social Media Data,” we examine the tensions in social media research between pursuing better science enabled by social media data and protecting social media users’ privacy. We focus our efforts on security and privacy research as it can involve sensitive topics such as misinformation, harassment, and abuse as well as the need for security researchers to be held to a higher standard when revealing vulnerabilities that impact companies and users.

Methodology

Toward this end, we conducted a systematic literature review of security literature on social media. We collected over 10,000 papers from six different disciplines, Computer Security and Cryptography (CSC), Data Mining and Analysis (DMA), Human-Computer Interaction (HCI), Humanities, Literature & Arts, Communication, (HLAC), Social Sciences, Criminology (SSC), and Social Sciences, Forensic Science (SSFS). Our final dataset included 601 papers across 16 years after iterating through several screening rounds.

How do security researchers handle privacy of social media data?

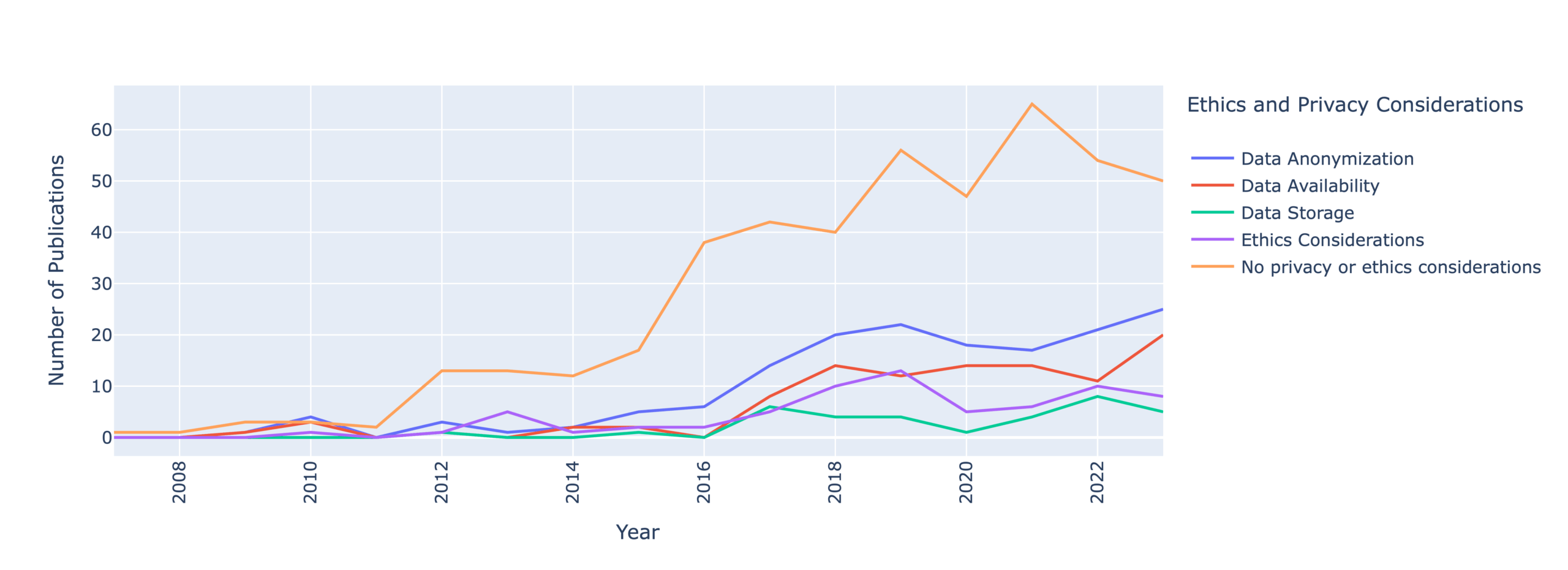

Our most alarming finding is that only 35% of papers mention any considerations of data anonymization, availability, and storage. This means that security and privacy researchers are failing to report how they handle user privacy.

This figure shows that, despite growing research outputs, researchers are increasing failing to report privacy considerations.

What privacy risks emerge from security research using social media data?

We uncover 11 privacy risks when researchers use social media data. These risks persist across the entire research process–from data collection to publication. We developed these risks by adapting Solove’s taxonomy of privacy based on our findings of how security researchers handle the privacy of social media data. Below, we briefly review these risks and how they manifest.

Information Collection

- Surveillance: Even though social media data is public, data collection methods, such as web crawlers and APIs, enable the recording, studying, and storage of users’ data beyond their intended purpose.

Information Processing

- Aggregation: Different social media platforms have different contexts. What is expected in one may be prohibited in another. Aggregation demolishes the boundaries between different platforms and enables more sensitive inferences to be made.

- Identification: Social media sites implement identification in a variety of ways: real-names, anonymity, and pseudonymity. Collecting data across platforms can lead to the identification of a user through methods via machine learning and stylometry.

- Insecurity: Despite its public nature, researchers should handle social media data as other private information due to other privacy risks such as surveillance and identification.

- Exclusion: When researchers only treat social media as bits, they strip users of autonomy over their own data.

Information Dissemination

- Disclosure: Sharing social media data in a publication may give increased attention to a private subject matter and may release sensitive information that embarrasses.

- Increased Accessibility: Collected social media data may remain publicly available for years after collection, exposing users in that data to “potential future risk.”

- Blackmail: Social media data may often include embarrassing or sensitive information. Researchers risk being blackmailed or enabling blackmail when they disseminate their outputs. This risk is exacerbated when combined with other risks, such as aggregation and identification.

- Distortion: The way researchers analyze or disseminate their research may impact perceptions of users or communities. It is important for researchers to reflect how their biases and decisions impact their study.

Invasion

- Intrusion: The Internet allows researchers to easily find any online community or groups. However, entering these digital spaces without proper training or experience increases the risk that research disturb users.

- Decisional Interference: Beyond disturbing online communities or groups, researchers may directly affect the relationships people have with one another and the social media platform. Researchers may create or exacerbate existing tensions within groups or highlight ways that platforms can further marginalize vulnerable voices.

How do security researchers mitigate privacy risks?

There is no silver bullet that will mitigate all the above risks. There isn’t even a single solution for mitigating each individual risk. Instead, we found researchers around the world are developing novel methods for making their social media research more privacy-conscious. These solutions come with trade-offs, but are nonetheless steps in the right direction.

Let’s look at the risk of identification. Information about a user, while not directly linked to their person, may be enough to identify them—for example, a user’s first name, gender, and date of birth are enough information to identify a single individual.

Machine learning methods, 55% (n=332) of papers in our dataset, are uniquely open to identification risks as researchers often deploy ML to make inferences across large datasets.

Identification is most commonly mitigated through data anonymization: removing personally-identifying information to ensure data cannot be linked to an online or offline user. Nevertheless, only 26% (n=158) of papers reference data anonymization—either in the text of the paper or in the dataset used. Of those, 60% (n=95) use anonymized data, 36% (n=57) use non-anonymized data, and 7% (n=11) use both anonymized and non-anonymized data. Disconcertingly, 11% (n=17) used data where individuals can be re-identified.

Data anonymization prevents simple identification but does not prevent more complex identification techniques. Today, researchers can use data modification or perturbation techniques, which maintains the main concepts or results of the data without providing an exact copy by modifying the data.

Trade-offs exist to anonymizing data or using more advanced anonymization techiques. Certain public figures will always be identifiable. In these cases, avoiding identification provides little to no benefit while requiring more work from researchers.

Where do we go from here?

We now know that there is a a severe lack of transparency around how security researchers handle the privacy of social media data. We also know that privacy risks abound depending on the platform studied, where the data comes from, the analysis methods, and how the data is published. Drawing from our findings, below we review what researchers, institutions/venues, and policymakers can do to preserve user privacy:

For Researchers

- Prioritize clear and inclusive risk disclosures: Identify all relevant stakeholders—platforms, users, and communities—and develop tailored, transparent communications about privacy risks.

- Evaluate and document third-party data practices: Before using third-party tools and datasets, assess their access controls, data handling policies, and potential for harm. Clearly justify their use in your methodology and ensure compliance with ethical and legal standards.

- Implement robust and resourced data storage plans: Allocate resources early for secure data storage, including encryption, controlled access, and infrastructure for long-term data protection. Report storage practices in your research to promote accountability and replicability.

For Institutions and Venues

- Strengthen IRB literacy on digital and social media research: Advocate for IRB training that addresses the specific privacy risks of social media data—particularly its semi-public nature and reidentification potential—even when research appears to qualify for exemption.

- Push for clearer ethics review documentation: Advocate for journals and conferences to adopt consistent, enforceable guidelines on social media data privacy—ensuring ethical rigor without deterring vital research on sensitive topics.

- Empower reviewers to assess privacy thoughtfully: Encourage reviewers to critically evaluate privacy practices without using them punitively, recognizing the need for flexibility in research design—especially for work involving marginalized or stigmatized communities.

For Policymakers

- Create researcher-specific guidance: There is a need for clearer guidance on how researchers can comply with privacy regulations when using personal data, such as consent, the right to be forgotten, and data storage. GDPR Art. 89(1) introduces some exemptions for scientific research, provided that the erasure would impede achieving the research purposes. However, it is unclear what this means in practice.

- Funding requirements: Funding agencies should consider requiring researchers to document their data privacy considerations, risks, and mitigation strategies when working with social media data. This should not be cause to cease or restrict funding, but as a way of shepherding researchers toward more considerate research design.

Acknowledgments

This work would not be possible without my incredible co-authors: Kieron Ivy Turk, Aliai Eusebi, Mindy Tran, Marilyne Ordekian, Dr. Enrico Mariconti, Dr. Yixin Zou, and Dr. Marie Vasek.

Photo by Stockcake